In a dramatic gesture hailed as bold and possibly useful, the Ugandan government has announced a three-year tax holiday for start-up businesses owned exclusively by Ugandan citizens provided they manage to survive the labyrinth of bureaucracy, unstable power supply, and regulatory whiplash.

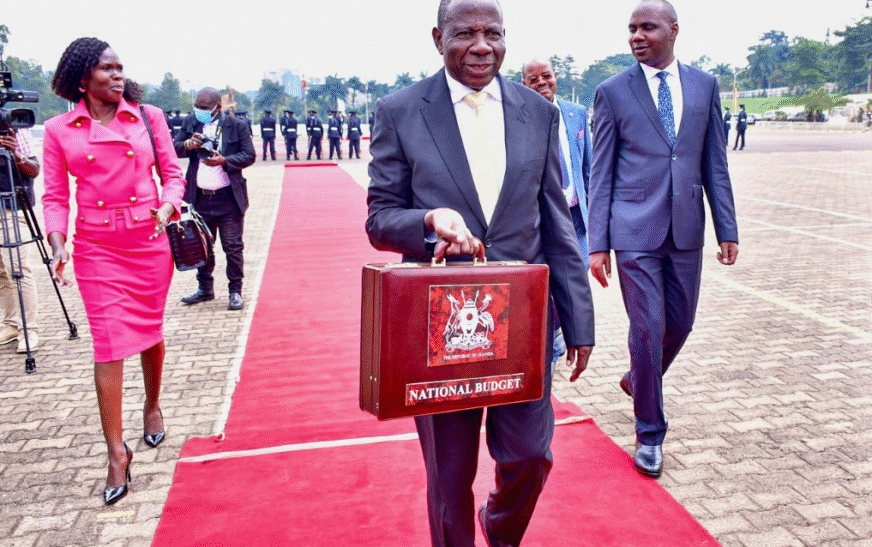

The announcement was made by Finance Minister Matia Kasaija while unveiling the Shs 72.4 trillion national budget, designed to appear pro-growth while still squeezing an additional Shs 538.6 billion from the same overburdened taxpayers.

“This tax holiday is our gift to you. In return, we ask that you build your company from scratch, employ hundreds, and comply with all digital systems we barely support ourselves,” Kasaija said.

The policy, effective for businesses formed after July 1, 2025, targets start-ups wholly owned by Ugandan nationals, a move critics claim could discourage foreign partnership, expertise, and capital, while encouraging creative paperwork to meet the criteria.

To further incentivize growth, the government has scrapped stamp duty on mortgages, conveniently forgetting that most Ugandans can’t afford mortgages in the first place.

Other relief measures include: Removal of capital gains tax on assets transferred to companies you already own (useful for those with assets meaning not you).

Extension of penalty waivers on outstanding taxes, so long as you magically pay everything else you owe within the next 12 months during a period of declining disposable income and high inflation.

On compliance, the government has softened EFRIS penalties from a flat Shs 6 million per error to double the tax owed, leaving businesses relieved until they realize how much they still owe.

In what seems like a gift to the health industry, excise duties on cigarettes have been raised, while beer brewed with local barley is now tax-free effectively promoting local alcoholism over foreign tobacco addiction.

In agriculture, a new export levy on maize bran and wheat bran has sparked fears among millers, but the government insists it’s meant to encourage value addition—a goal that remains largely theoretical.

Meanwhile, textile importers have been thrown a bone: duties on fabrics and garments have been slightly reduced, possibly helping traders survive another month if global shipping costs and local corruption don’t eat them alive.

“These changes reflect our ongoing commitment to confusing the average citizen while pretending to empower them,” Kasaija said.

To fund the rest of the budget, the government will borrow Shs 24.79 trillion both locally and externally, because apparently, debt is still cheaper than listening to economic advice from actual entrepreneurs.