By Christopher Burke

Uganda’s urban population is rapidly expanding and nowhere is this more visible than in Kampala. The capital city has experienced significant growth in informal settlements over the past two decades, driven largely by young people migrating in search of employment and affordable housing. Today, an estimated 60 percent of Kampala’s population lives in slums or unplanned areas where land tenure insecurity limits access to services, finance and long-term opportunity.

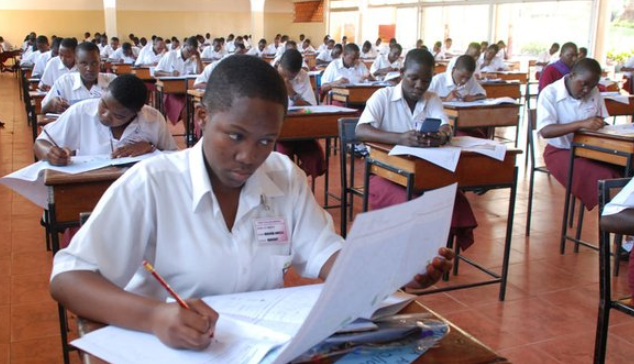

The 2024 National Population and Housing Census reported that approximately 42 percent of Uganda’s total population of 45.9 million is under 14 years. Adolescents (ages 10-19) account for 25 percent of the population while youth (ages 18-30) make up 23 percent. Though disaggregated urban data is scarce, a 2017 UNFPA report estimated that 32 percent of youth aged 15–24 live in urban areas; significantly above the national average of 24 percent. Many of these young people, especially those new to the city, settle in densely populated informal areas lacking basic infrastructure like waste disposal, electricity or paved roads.

Uganda’s dual land tenure system comprising statutory and customary tenure adds a layer of complexity. Over 75 percent of land is held under customary tenure, including peri-urban zones around Kampala. The process of formalizing land rights can cost upwards of UGX 1.5 million, including stamp duty, registration and survey fees. Many youth simply cannot afford this. Instead, they rely on informal proof of tenure such as rent receipts or letters from Local Councils that offer no legal protection in the event of disputes or evictions.

Evictions from informal settlements are not uncommon. In places such as Nakivubo Channel and Banda Hill, households have been removed with minimal notice and compensation. Data is limited, but evidence suggests young women are particularly vulnerable. A recent study in Kampala found gender norms and power imbalances expose young women in informal sectors to sexual harassment and evictions, particularly in the absence of adequate documentation.

According to Simon Peter Mwesigye, coordinator of the Land at Scale project in Uganda with UN-Habitat Global Land Tool Network (GLTN), mapping exercises using the Social Tenure Domain Model (STDM) and participating enumeration approaches have effectively helped young people in informal settlements secure formal recognition of their land rights and access to basic services. He adds that “access to secure land rights is more than ownership; it is fundamental to youth livelihoods and well-being including improved housing, living conditions and productivity.”

Without a stable living environment however meagre, young people are less able to plan, invest or contribute to the urban economy. Sam Mabala, former Commissioner of Urban Development at the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development (MLHUD) suggests the integration of youth-focused provisions into urban land-use policies is essential to ensure meaningful participation and long-term planning.

Environmental vulnerability compounds tenure insecurity. Many informal settlements are located on wetlands, floodplains or steep slopes. A study on the Nakivubo wetland found a 62 percent loss in vegetation between 2002 and 2014 largely associated with unregulated construction and cultivation. These conditions heighten the risk of flooding and health hazards such as cholera and respiratory diseases, particularly in homes that rely on charcoal or paraffin for energy.

Tenure insecurity also discourages investment in sanitation and shelter. Without legal protection, few are willing to upgrade homes or infrastructure. The lack of formal documentation further restricts access to credit. The Uganda Microfinance Regulatory Authority’s 2023 National Financial Inclusion Strategy acknowledged that youth in informal settlements face high loan rejection rates due to a lack of collateral, credit history and informal employment. Many are forced to pay inflated prices for water and electricity through unregulated intermediaries. Small business operators struggle to grow and formalize ventures.

Technology presents new tools. Advances in drone mapping, participatory digital platforms and open-source spatial data tools are enabling communities to generate and manage accurate land information. According to Mikkel Aagaard Harder of Slum Dwellers International, such initiatives in Sierra Leone have been implemented at modest cost, demonstrating the feasibility of replicating such innovations in Kampala and beyond.

Municipal governments are starting to act. In Wakiso and Mukono Districts, youth representatives now serve on Village Land Committees. Organizations such as Namati Uganda have trained youth paralegals who mediate land disputes–more than 300 cases to date–often involving eviction or boundary issues. In Kampala, anecdotal evidence suggests that “Youth Land Forums” are helping bridge the gap between young residents and district land boards, improving transparency and responsiveness.

Michael Ayebazibwe, Executive Director at ACTogether Uganda, emphasizes the importance of a three-pronged strategy: supporting youth livelihoods through savings groups, enabling community-led data collection and building grassroots advocacy for slum upgrading. Data alone is not enough—it must be linked to the organization of communities and local leadership to create real change.

Ensuring that young people have a voice in designing land regularization programs strengthens their tenure security and builds a sense of ownership and belonging. Mara Forbes, Urban Development Specialist at Cities Alliance, agrees integrating young people into planning processes contributes to more inclusive urban development.

Gender is a frontline issue in urban land governance. Advocacy by groups such as Uganda Women’s Network (UWONET) and Uganda Land Alliance (ULA) led to key protections in the 1998 Land Act, including spousal co-ownership provisions. Gaps in implementation persist. Customary tenure arrangements can be manipulated to exclude women, particularly unmarried mothers, from land access.

Innovative responses are emerging. In Entebbe, Action for Liberty and Economic Development is working with the Buganda Kingdom and MLHUD in the implementation of a women-centered land titling initiative involving sensitization, participatory mapping and streamlined registration. The project demonstrated that securing land rights can enhance access to credit and catalyze investment in livelihoods. Urban agriculture presents a promising entry point for young women to secure land use rights and improve their income. These themes are echoed in policy-oriented literature, including recent work on youth and land by development practitioners across Kampala.

Despite the progress, challenges persist. Informal land markets can be highly complex and invariably opaque. Middlemen regularly demand advance payments in exchange for promises of documentation. Driven by demand and speculation, rocketing land prices in peri-urban areas push youth to more marginal and less accessible areas where infrastructure is often inadequate. Narrow, unplanned roads impede movement and service delivery while the absence of formal zoning impedes upgrades. Planning is imperative. Chris Cripps, a senior physical planner and former advisor at MLHUD and the World Bank in Uganda, argues aligning spatial planning with youth tenure needs is critical to fostering equitable and sustainable urban growth.

Uganda’s youth dominate the urban demographic landscape. Insecure tenure keeps many locked out of economic opportunities. Many observers across government and civil society agree new legislation is not the most urgent need. The desperate lack of resources and political capital to implement existing policies, simplify procedures, reduce costs and enable youth-led innovations remain core challenges.

Secure land tenure will not solve everything, but literally provides a sound foundation. Investments in participatory planning, data systems and youth capacity-building can pave the way for fairer, more inclusive cities. Empowering Kampala’s youth through secure tenure is not charity, but a strategy for smart, sustainable development.

Christopher Burke currently serves as senior advisor at WMC Africa, a communications and advisory agency located in Kampala, Uganda. With almost 30 years of experience, Christopher has worked extensively on social, political and economic development issues focused on governance, the environment, agriculture, public health, extractives, communications, peace-building and international relations in Asia and Africa.