Africa is home to nearly a fifth of the world’s population. Yet it produces just three percent of global scholarly research.

That imbalance — stark, statistical and symbolic — framed a conversation at Makerere University last week, where leaders signaled a renewed ambition: shifting the continent from the margins of global knowledge production to its centre.

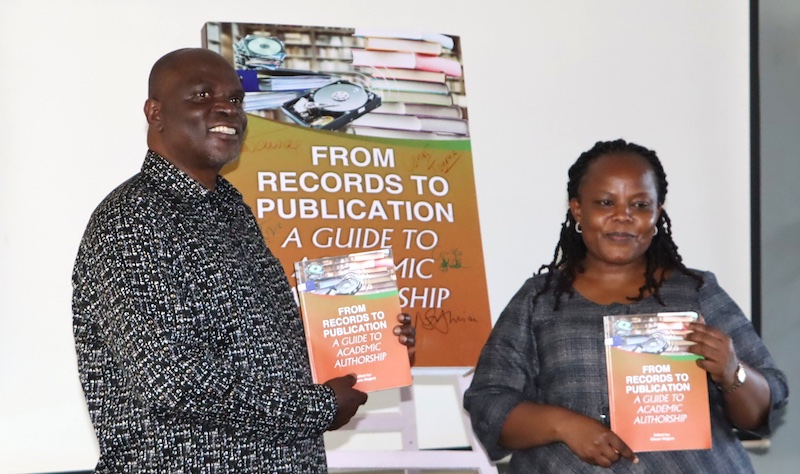

The occasion was the launch of From Records to Publication: A Guide to Academic Authorship, edited by Elisam Magara. But the subtext ran deeper than a book release. It was about intellectual sovereignty.

For decades, African scholars have researched epidemics, climate shocks, governance systems, migration and development. Yet much of that work has remained locked in lecture rooms, internal repositories and conference halls — produced, but not powerfully published.

“We still publish only three percent of all publications in the world,” Vice Chancellor Barnabas Nawangwe said. “Yet our population will contribute 15 percent.”

To Nawangwe, the disparity is not accidental. It is historical.

“Slavery was there for 400 years, followed by 200 years of colonialism. So, 600 years of subjugation. You cannot just brush that away,” he said.

But history, he argued, cannot remain a permanent alibi. Development today is anchored in knowledge production. Countries that dominate research often shape global policy, control innovation ecosystems and influence economic trajectories.

Makerere’s own trajectory offers a glimpse of what is possible. A decade ago, the university produced roughly 500 academic publications annually. Today, it generates more than 2,000. Its international research footprint has expanded, but university leaders acknowledge that structural barriers persist. One of the most significant is publishing infrastructure.

“Why can’t we have our own journals?” Nawangwe asked, urging colleges to revive dormant publications or establish new ones under Makerere University Press.

The question speaks to more than institutional pride. Academic journals determine whose knowledge is validated, how it is framed and who benefits from its circulation. Reliance on European and North American platforms often leaves African scholars navigating external gatekeeping systems.

Magara’s book intervenes at a critical point in that chain — authorship itself.

Conceived in 2022, the project began with an international call for abstracts that drew about 30 submissions. Contributors participated in a write-shop, followed by at least two rounds of peer review. To safeguard objectivity, chapters written by the editors were reviewed by three independent scholars.

Magara, a specialist in records and archives management, describes his role as architectural rather than merely editorial.

“My role was to organise what the authors had written and then plan which chapter comes first and which comes last,” he said.

A sabbatical granted by the Vice Chancellor provided the time needed to refine the manuscript — a reminder that research quality is often tied to institutional support.

Submitted in July 2024, the manuscript underwent rigorous checks at Makerere University Press, including copyright clearance, referencing audits and strict ethical review.

The finished volume contains 17 chapters divided into three sections: the foundations of academic writing; navigating the publication process; and building impact through mentorship.

It explores how ideas evolve into recorded knowledge, then into published scholarship. It addresses practical tensions — co-authorship disputes, translation, citation systems, publication costs and research metrics — while emphasizing collaboration.

“You will not write alone,” Magara said, underscoring the importance of guided academic growth.

International endorsement followed. Jorgen Lorentzen, International Secretary of the Norwegian Association of Nonfiction and Translators (NFFO), described the book as a reflection on writing as practice and publishing and reading as its essential companions.

Yet beyond the endorsements and statistics lies a broader strategic calculation.

In the modern world, knowledge is currency. It influences trade negotiations, climate frameworks, pharmaceutical patents and digital governance. Regions that generate data and scholarship often set the terms of debate.

Makerere’s message is therefore not merely academic — it is geopolitical. Africa must not only research its realities. It must publish them, own them and circulate them on its own terms.

Because in the global knowledge economy, authorship is power.