In what is shaping up to be one of Uganda’s most tightly controlled election cycles in recent memory, the Electoral Commission has cleared eight candidates to contest the 2026 presidential election.

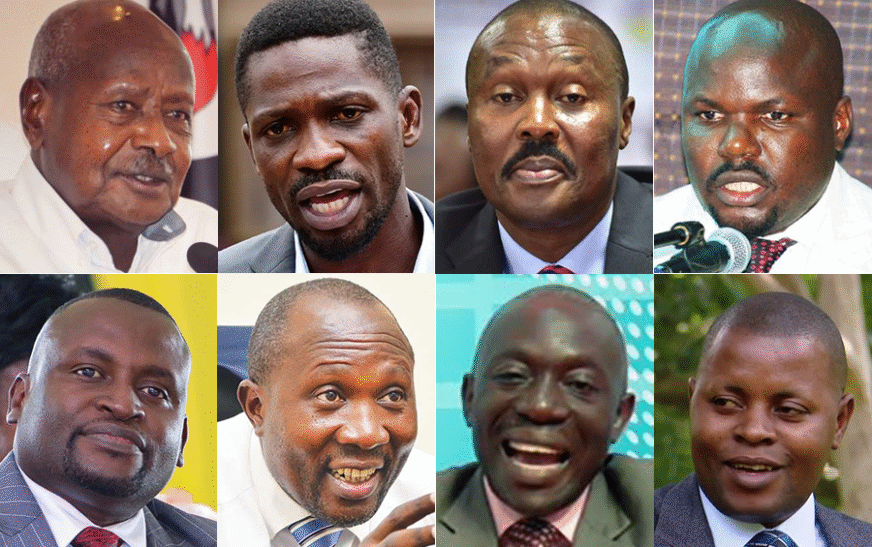

The eight include; Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu aka Bobi Wine (National Unity Platform -NUP), Yoweri Kaguta Museveni (National Resistance Movement – NRM), Elton Joseph Mabirizi (Conservative Party – CP) and Robert Kasibante (National Peasants Party – NPP)

Nathan Nandala Mafabi (Forum for Democratic Change -FDC), Mugisha Muntu (Alliance for National Transformation – ANT), Munyagwa Mubarak Sserunga (Common Man’s Party-CMP)and Bulira Frank Kabinga (Revolutionary People’s Party- RPP)

This final shortlist stands in stark contrast to the 220 individuals who picked nomination forms earlier this year, raising serious questions about accessibility, transparency, and the evolving architecture of political participation in the country.

Missing from the race are not just the usual fringe hopefuls, but former presidential candidates like John Katumba, Joseph Kabuleta, Willy Mayambala, and Nancy Kalembe, all of whom were deemed ineligible under the EC’s nomination process.

Their disappearance from the final lineup has been met with a mix of silence, confusion, and concern not least because the Electoral Commission has offered little clarity on the disqualification criteria for several of the more prominent names.

At face value, the EC’s weeding-out exercise may appear to be an effort to streamline an overcrowded field. But a deeper look reveals the uncomfortable truth: less than 4% of those who expressed interest even made it to the starting line.

Of the 220 who picked nomination forms, only 38 returned them. And out of those, just eight crossed the threshold. According to EC spokesperson Julius Mucunguzi, the Commission is demanding accountability from the 190+ who never submitted their forms citing wasted public resources and administrative strain.

The complete absence of female candidates is perhaps the most telling reflection of the election’s narrowing scope. Since Miria Obote’s historic bid in 2001, women like Beti Kamya, Maureen Kyalya, and Nancy Kalembe have carried the torch of female leadership into the presidential arena often facing slim odds and steep skepticism.

Now, for the first time in nearly two decades, no woman will appear on Uganda’s presidential ballot.

The implications go far beyond symbolism. It signals a political environment where the structural, financial, and social costs of running for president are increasingly out of reach especially for women and independent voices.

In a nation where women make up more than half the population, their exclusion from the highest contest in the land speaks volumes about how far gender parity still has to go.

With the official list of candidates expected to be gazetted in the coming days, the 2026 campaign season is officially underway. But it begins under a cloud of unresolved questions: Why were so many aspirants unable to return their forms? What criteria disqualified experienced candidates? And perhaps most importantly who gets to decide who qualifies to lead?

For now, the field is set: eight men, eight political machines, and one very silent question mark over the democratic health of Uganda’s electoral process.

As rallies begin and manifestos are unveiled, the spotlight will inevitably shift to campaign promises and polling numbers. But beneath the surface, the deeper story remains: Uganda’s path to 2026 may not be about who runs but who gets to run at all.